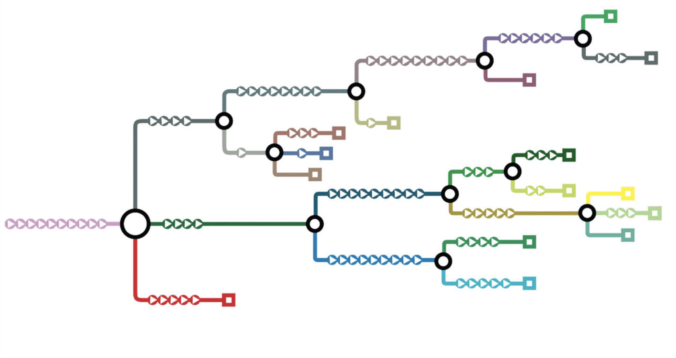

From an Educators point of view, curriculum to me is a ‘choose your own adventure’ book. We are presented with a laid out framework of where students are intended to be at the end of each school year and we get to choose the direction we take that in. As you do in an adventure book, you must decide the direction you are going. I see those decisions as what learning intentions are essential for that cohort, what order to teach them in and what teaching strategies I use to facilitate student learning on the way. The importance here is not the ending, but how we get to the final intention. From my experience we often get totally off course or find ourselves in a chapter we didn’t intend to be in but learn so many other intentions along the way. These side tracks or adventures within a chapter are an overarching idea where students are taking autonomy of their learning and teachers are helping to facilitate a student centered approach. My background includes teaching in Australia for six years at a Special Development school with a range of ages alongside Kindergarten, Grade one and Grade two at public schools. The range of learning outcomes for these age groups tend to be very similar across all curriculums as the focus is the fundamentals of reading, writing and counting. My observations of student learning occur so much outside of curriculum documents and take place during exploration, social problems during play, dialogue with friends during lunch and conversations with adults about their weekends.

I have always wondered who makes curriculum, how they decide what is important, and knowing when students need to be at what level. I’ve wondered why we prioritize and worry about learning certain things that lack relevance to students’ futures and interests and how teaching from a textbook can help to ruin a students passion for something they thought was interesting. As a primary school teacher, changes and decisions to move towards a constructivist approach including student centered learning and teacher as a facilitator has been exciting over my short career. These movements have shown growth towards respecting individual differences, abilities, nurturing curiosity and risk taking in the classroom.

The top down approach from Universities is a concern as stated in Blades article in response to change, reform and revisions. The desire for power and the need to be a part of the science curriculum change in Blades article made it extremely frustrating to understand why changes didn’t move forward, and who was being thought about in the decision making. Student learning seemed to be at the very bottom of the decisions being made and the bureaucracy of education made making simple changes almost impossible from the top down. The challenge I see is not only the bureaucracy controlling the outcomes, but also the lack of inquiry nature educators are employing that we are seemingly pushing on students but not using ourselves. Change is not meant to be clean, simple or easy. The idea that we have the answers or know what is best for students is the same as saying we know what the world will look like in ten years. The changes we have seen in 2020 are a reminder of this in that problem solving, adaptability and critical thinking are crucial for navigating the future. While discussing all of these ideals, the child entering into the room in Blades’ article who needed help was another attempt or outreach of students trying to take control of their learning and pathways. As stated by Egan, “Sir, while you stand considering which of two things you should teach your child first, another boy has learnt ’em both” (Pottle, 1950, as cited in Egan, 1978, p.11). As the power struggle continues on what is best for students, the need to look to the learners for answers becomes more and more relevant.

References

Blades, D. (1997) Procedures of Power in a Curriculum Discourse: Conversations from Home. JCT, 11(4), 125-155.

Egan, K. (2003) What is Curriculum? JCACS, 1(1), 9-16.

Leave a Reply